Top Five Luciëst Game Genres

Posted on

I like video games. They're fun, they're artistic, and each of them is a labor of love. I'm glad to be saying this in a time when people who talk openly about playing video games aren't ostracized and where people don't debate anymore whether video games are art, because that's a hostility and alienation they just don't deserve.

Just like with any other form of art, asking someone about their genre tastes is a lovely question for learning more about them as a person. And that's the question through which I want to lend you, dear reader, a little lens into my mind. Though rather than talking about what kinds of games I like the most or play most often, I'll talk about what characteristics make a game especially Luci.

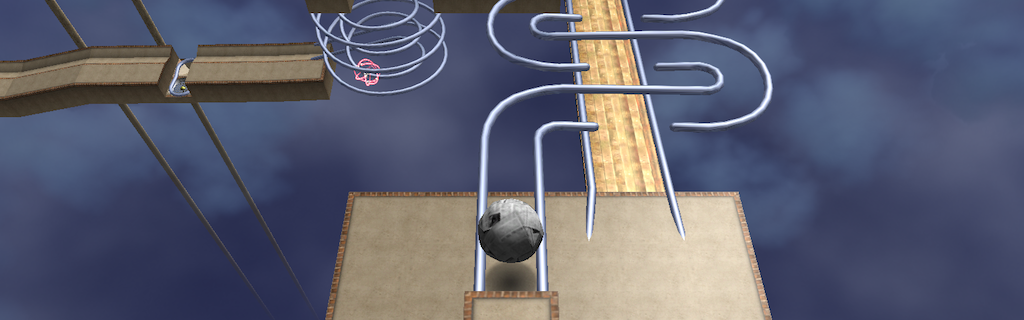

Rolly ball games ↥

“Roll a ball from point A to point B” is an adorably simple premise. And yet – or maybe and so – it's this very premise that conquered the young hearts of many a kid first discovering the world of video games, myself included.

Games that follow this premise don't have a universally agreedüpon name; you'll see them variously referred to as ball games, marble games, rolling ball games,jump to footnote and probably more. I settled on calling them ‘rolly ball games’ after my friend Addy, a fellow lover of the genre, who I actually met through our shared interest for it. I love how her the whimsicality of the term feels. And I won't say no to the near-rhyme.

Excluding Flash games hosted on websites targeted specifically at kids, the first actual video game I've ever played was a rolly ball game: Ballance, a veritable fever dream from 2004. Ballance is a weird enough experience that it easily trumps other games of the genre, and it's sure to leave a mark on your mind even if it's not your first time ever seeing a video game – let alone if it is. The stark reälism of the sound and feel of physics objects pushing and colliding with each other clashes viölently, but so beautifully, with the fantastical surreälism of the setting – geometric structures in the sky, so impossibly high up that the towers supporting them fade out into the atmosphere long before you could see them end. And not just the setting, but the level elements are surreal, tooz: the picküps that grant you extra lives and time points aren't fully gamified, but rather exist in a limbo between fitting in and feeling starkly out of place, halfway between real and ethereal. The interäctions between the player's ball and the levels' various machines are physically absurd, but aren't tucked away under the rug of suspension of disbelief by being labeled as magic, either: these impossible contraptions are presented withöut any theätrics, as if they were the most normal thing. You end up with something truly unforgettable even if you didn't still go on to combine all this with an original soundtrack that doesn't sound like music at all, but rather more like an imitation of ambient wind sounds with musical instruments.

And the advent of my experience with video games didn't stop at Ballance, either. It shaped my mind massively, but it was just the beginning of a veritably neurodivergent rolly ball craze. The next game I played was Switchball, a rolly ball game. And then Puzzle Dimension, a rolly ball game. And then Neverball, Hamsterball, Marble Blast Gold, BlockBall Evolution, …you get the idea. Heck, not even a terribly overpriced Shockwave game with abysmal level design could escape my attention and my willingness to take it at face value. Who knows how much longer my gaming repertoire would consist exclusively of games with “Ball” in their names if YouTube's Almighty 'Gorithm hadn't shown me Minecraft.

I think the spirit of these games has a beautiful charm to it. Infusing an inänimate ball with life essence is an act of childlike imagination like no other. I can attest to that, with the dozens of times I pretended to be playing a rolly ball game as a kid in a furniture store. Addy can understand, tooz. Many modern rolly ball games which are either homages to the legendary piöneers of the past (Ballex, Marble Race) or the result of perfecting an idea after many iterations (PlatinumQuest, Marble It Up) add to the charm even more, reminding players like me of their own childhood dreams to creäte their own countless rolly ball games.

And so it happened that this silly genre has stuck around with me throughöut all these years. Rolly ball games have been at my side through middle school, high school, and university. And although the genre as a whole evolves – graphically outdoing itself, no longer needing to cut corners for performance's sake, embracing more of an arcade aesthetic – its heart has remained unchanged since the days of Ballance: the beautiful surreälism that doesn't draw any attention to itself and hides so well behind the umbrella of suspension of disbelief that eventually you don't even question that this ball can jump of its own volition.

Logic games ↥

I like games about solving puzzles. That's essentially what logic games are, except that the term ‘logic game’ narrows the category to games in a sci-fi setting where the puzzle elements are implemented with machines. Games like Portal 2, Q.U.B.E., Relicta, the Rethink series, The Last Cube, or The Talos Principle 2 (pictured above) are good examples. Nonëxamples, puzzle games that aren't logic games, would be games like Baba Is You, I Wanna Lockpick, or Patrick's Parabox – which I also like, they're just a different genre to me.

The distinction between logic and non-logic puzzle games is one that matters to me, which I suppose makes logic games an ‘idiogenre’. I have many idiogenres, and idiogenres make up the majority (or even all, depending on how you see it) of the categories of games listed here. And the answer to why this particular idiogenre exists is probably more in my history than in an objective rationale of any kind.

My tweenäge years were heavily shaped by Portal 2, the direct successor of Portal, itself one of the piöneers of the logic game genre as a whole. It was both an enormous outlet of my level-designing creätivity and a far too direct source of inspiration for dozens of ideas for spiritual sequels. Even before the Perpetuäl Testing Initiative, Portal 2's builtïn level editor, I'd already drawn hundreds of Portal puzzles in my notebooks, which were only followed by even more once I got my hands on the power of the editor. And I'd planned out tons of imaginary games and built tons of abandoned Minecraft adventure maps which all had the same plot line and the same setting, just with slightly different puzzle gimmicks every time. There was one about skewing rectangular blocks into parallelograms. One about “saving” and “loading” the puzzle state. One about switching between two ever so slightly different versions of the same room. One about Minecraft 1.10's new feature to pull items with fishing rods. And at least four or five iterations of one about controlling two bodies but moving only one at a time. There was even one about nothing in particular, just generic puzzles. What they all had in common was their setting: a facility full of ‘test chambers’, which even often numbered exactly or nearly twenty, the same number as in Portal. They were all Portalidos.

I devoted hundreds of hours to those abandoned pseudogames, and hundreds more to Portal 2 itself, getting lost in the jungle of its community workshop, exploring its pearls of artfulness and absorbing them like a sponge. It was a wild time, a time of the young, not-yet-well-defined Luci whose own creätions from that era were more or less just distorted, kitchensinked reflections of the input she received.

But it's precisely for that reason that the influënces from that time were so strong in shaping the Luci of the present. And this Luci is glad they were there. They gave me almost a decade's worth of knowledge and skill in Minecraft modeling and command block programming.jump to footnote

Some of my passion for inventing logic games survived until today, in a handful of game ideas which I'd probably make a reälity if I knew more about game development than I do about programming in general, and if I was more willing to put time and energy aside from my projects in other fields to pursue a serious game project. Izzi and the Rainbow Cube and the project I gave the codename ‘DCM’ are ones whose hope I haven't given up yet. If logic games shaped so much of me, the least I can do in return is give them an homage the Luci way.

Starleaping games ↥

Skyrim is such a legendary meme game. So wacky that at times it feels like all its NPCs are pulling the biggest coördinated prank on you, trying to sound dead serious talking about their own goofy fantasy world only to burst out laughing the moment you leave the inn.

A few other starleaping games I like are like this tooz. Maybe the gamification is so strong that it makes the worldbuilding inconsistent, maybe the tone of the writing is bad, or maybe just the limitations of the game engine reveal themselves in the blurry low-pixel texture of the ground. And yet I have a tendency to forgive games for flaws like these particularly easily if they belong to this one particular genre.

‘Starleaping’ is another idiogenre of mine, like ‘logic’. The term is a Lucification of ‘world-hopping’, which in turn seems to be a fiction genre for stories where characters can seamlessly switch between parallel universes. Because that's what starleaping games let me do: switch to a parallel universe for a time. To imagine I'm somewhere else, in a world with entirely different rules. Usually, cooler ones.

Starleaping games are, by necessity, 3D first-person games in which the player character is broadly humanoid, often with a form of character creätor; and I let myself fully identify with that character. I don't generally roleplay – I don't put myself in the shoes of another, pretending to have a different backstory or different motives and beliefs. No, I imagine my real true self in the game. I can't really do otherwise; even the one time I played a tabletop RPG, my character was basically just me but adapted to the game's setting. It's not simply out of a lack of originality that I usually name my characters Lucilla – even in cases where, from a worldbuilding linguistics perspective, it's at best questionable.jump to footnote (But hey, maybe my headcanon is that my real self got magically whisked into this world. That would at least explain the lack of memories about my character's past.)

Maybe it's not a coïncidence that Skyrim, the first starleaping game I ever played, was significant to me at around the same time as the beginning of my interest in lucid dreams. When I was thirteen, I found Skyrim really cool. I could zash!jump to footnote I could shout some words in one of the worst conlangs of all time and make magic happen! Who wouldn't find that super fun?

I feel similar now about another starleaping game, Islands of Insight. I get to explore a place which is almost basically my childhood mental idea of heaven: the game world is a lovely, peaceful floating archipelago filled with near infinite puzzles to solve.jump to footnote And I get to fly! With wings! Well, glide, but close enough.

Starleaping games are the lucid dreams of gaming: that's the closest to what they feel like. They're excursions into alternate worlds where I can remain free and in full control, having fun with (usually) new abilities I can't otherwise have, withöut fear of any permanent consequences, and always able to return to the real world at will.jump to footnote

Is that escapism? Maybe. But I don't find it wrong. I'm not trashtalking or becoming detached from reälity, nor ignoring the game itself as a work of art. These games are my portals into awesome fantastical worlds, not out of the real world.

Starleaping games are simply fun. So fun that they're super easy to forgive for little mistakes. My imagination is already hard at work playing them in the first place; it can handle patching a few holes in the fabric. The benefit of the doubt is the least I can give them as my token of gratitude, for giving me a window into the impossible ever since I was a teenäger. This isn't love being blind; it's compassion being sighted.

And speaking of fun, the award for the most fun starleaping game I know of has to go to In Verbis Virtus,jump to footnote a silly little proof-of-concept game that I discovered so recently that I haven't even completed it yet at the time of writing. If shouting silly words in a silly conlang to zash in Skyrim was so fun, just imagine how fun it'd get if you could use your real voice to do that! Because that's exactly what this game lets me do. Ahh, the sheer power!

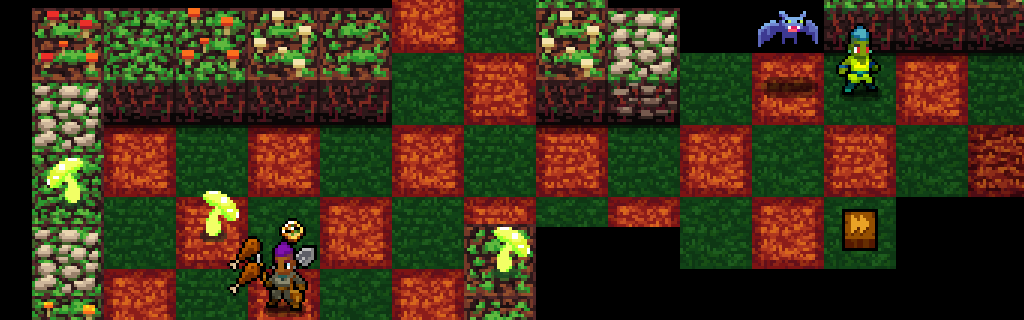

Secondary rhythm games ↥

Musicking is one of my lifebloods, so in theory it shouldn't come as a surprise that rhythm games are among the top five Luciëst genres. I've even explicitly talked about them in my earlier post about how I perceive music. But what's that dangling adjective doing there? What are “secondary” rhythm games, and what's the difference between them and, assumedly, “primary” rhythm games?

The easiest way to explain it is that I'm not a rhythm nerd. I can't hit dozens of notes per second. I like pushing buttons to the beat, but I'm nowhere near into the rabbit hole with it that I could play games like osu!. So I don't usually play games that are just about rhythm. I play games that mix rhythm in.

A secondary rhythm game (hey, yet another idiogenre!) is a rhythm game which is actually about something entirely different, with an additional rhythm mechanic thrown in to make it way more fun. It's always a combination of rhythm and some other genre. Take Crypt of the NecroDancer, a rhythm game which is also a turn-based roguelike. Or BPM: Bullets Per Minute, a rhythm game which is also a first-person shooter. Or the series that was my introduction to this beautiful world – Patapon, a rhythm game which is also a cartoony pillage-and-plunder tribal war simulator.

Another way to put it is that secondary rhythm games are ones where the rhythm inputs are not notes for their own sake, but a means to an end – usually to carry out some ordinary action. And there's something truly magical about doing “normal” actions to the beat! This time it's not even a peculiarity in my music perception, otherwise video edits that sync things to a song wouldn't be so popular. The charm of rhythmifying things is contagious enough that I remember a few cases of myself syncing digging dirt blocks in Minecraft to some music I happened to be listening to. So if watching a choreographed video is satisfying enough, then what can be said for playing a game that choreographs itself?jump to footnote

Perhaps the most surprising thing about this particular idiogenre of mine is that my history with it isn't all that old, compared to the three that came before it. All of those have been with me nearly the whole time I've known video games as a whole, but I had to wait until 2019 before I discovered the world of secondary rhythm games through Patapon. I'd only known about primary rhythm games before that, and I'd had no interest in them – maybe partially as a side effect of the classical supremacism I'd grown up in. To think how much I've changed since then.

Playing secondary rhythm games has expanded my horizon of musicking, and I'm grateful to them for that. They taught me, uh, “rhythmicality”. Musicality, but for rhythm. Before Patapon, my feeling of rhythm was kind of stiff, very handwavy, very theoretical – I didn't really feel rhythm, I only thought it. With Crypt of the NecroDancer, I gained the ability to dance, where before there were only half-paralyzed motions. Heck, it might not be the wildest claim to say that rhythm games were the prime mover that led to me discovering how my own music perception works – you know, all that ‘flair’ stuff.

You know, the lore of Crypt is that its monsters and the character are cursed to move to the beat of the music – what if that's also the lore of its players? I don't know about others, but ever since I've played it, I'm cursed to move to the beat of whatëver music I'm listening to. It's an awesome curse. I ain't lifting it.jump to footnote

Heartgames ↥

“Heartgames” is, by definition,jump to footnote the Luciëst possible genre. The most idio of idiogenres.

A heartgame is any game that is so powerfully Luci that it feels like it's made out of the same stuff as me. That it sprang out of my own core and awakened aspects of me hidden deep inside which I never knew existed. These games are nothing short of transformative, and they have a fixed spot in my history and my memory for that. Given all that, heartgames are extremely few – at the time of writing this post, no more than five, depending on how you count.

These are two heartgames I'm particularly fond of. They have each had an especially powerful effect of marking a dividing point in the development of Lucilla as a person. Each of them is worth their own entire post, to be frank – and will probably eventually get one – but the least I can do is try to summarize what each of them mean to me.

These two little stories are probably the most vulnerable points in this entire post. I trust that if you've made it this far, you'll appreciäte the courage it took to put these here for you to read.

Kind Words. ~ This adorable little game and its successor, Kind Words 2, are hardly games at all. They're more like an anonymized social media network that consists (mostly) of writing kind letters to strangers in response to requests. When this game popped up out of the blue in my Steam queue one day near the end of 2019, in such stark contrast to the lifeless, samey stuff that I was used to seeing, I was nothing short of positively startled. It was as though it activated something deep inside of me that instantly knew, even though I'd never done anything like this before, that this was a job for me. How little did I know in that moment that I had just ignited the spark that would flourish to become one of the core aspects of my personality. If I were to say in one sentence what happened in that moment, it was this: I heard the calling to become an emissary of good, and I answered it.

One Hand Clapping. ~ Fast forward to late 2022, and another lucky encounter in the midst of the Steam jungle lands me on this wonderful game. This 2D musical puzzle platformer that requires you to sing to solve its puzzles came to me at just the right time when I was flipping the way I feel about my own voice upside down – or more precisely, downside up. Withöut the beautifully encouraging environment of its cute little characters and the powerfully visible effects of my voice on the game world, I would never have had such an easy and rewarding time experimenting with singing after a lifetime of Silence. And not only did this game open me up to a new, viscerally jovial kind of musicking, the way this game's world looks is just so Luci – as if it was taken right out of my mind. I mean, it has a desert of purple sand, there are floating rocks, the characters hug me, and I even get to fly controlling my altitude with the pitch of my voice! I wouldn't mind spending a day or two in its world, that's for sure. And yes, this game's emblem, the square spiral, made its way into my profile picture.

Honorable mentions ↥

As a bonus, here are some more idiogenres of mine that didn't make the cut to the top Five:

- Flow games. Ah, if it isn't Mihály Csíkszentmihályi's concept of flow. I really enjoy games that can lock me in on a high-precision activity and have me pull off chains of crazy tricks after dozens of failed attempts. My fingers are really good at learning these, and I feel little to no frustration from trying over and over. The main reason I excluded this category is because the only flow game I've played so far that isn't also either a rolly ball game or a secondary rhythm game is Celeste.

- Beauty games. These are games about creäting negëntropy in some sense, games that make me control them to the very last detail. This idiogenre is defined very abstractly, but currently, sandbox games – especially Minecraft – are the only examples I can think of.

- Housewiving games. Probably the most popular representative is Stardew Valley.

- Zachlikes. This label – derived from the indie game studio Zachtronics – sees some very niche recognition outside my own Steam library. It refers to open-ended problem-solving games where players engineer the solution to some specification, usually with a focus on optimization. I haven't played these recently, but they did leave a mark on me in the form of inspiration for one or two esolangs.

Footnotes

- As in the name of the youtube channel Rolling Ball Games [YT]. ↩

- Why do you think I made that one assembler? ↩

- This once made me massively confused about a quest in Skyrim, funnily. The quest Blood on the Ice involves a somewhat creepy journal entry mentioning Lucilla, which – based on the hundreds of letters the player receives – I'd assumed was the player's name when I discovered it in-game. But nope, this one time it was actually a hardcoded name of an NPC. (At least she wasn't called Luci for short.) ↩

- Zash is a custom word of mine (idioword?), a verb meaning roughly ‘cast spells’ or ‘make magic happen’. Many other languages have a single basic verb for this. ↩

- And I'm not the only one who feels this way: Tyler from Aliensrock agrees (timestamped link). ↩

- To be Clear, this isn't exactly a fair comparison. Starleaping games are more like the poëtic, ideälized image lucid dreams have in Popular Culture. ↩

- Its name loosely translates to “words have power”. (Working my way through LLPSI has paid off! And it's left a permanent mark on me: I can't unsee the macron in ‘verbīs’.) ↩

- I can't speak for myself, but I was awestruck when I first saw this gameplay video of BPM from IGN. I was so enchanted that I was sold on a game from a genre I'd never played nor liked before – first-person shooters. ↩

- My “curse” actually has one more component to it: when I tap along to a rhythm, I tend to skip every eighth beat. I have the Shrine of Rhythm to thank for that. ↩

- I have a bit of a pet peeve with the phrase “by definition” when it doesn't actually mean by definition, but rather something like by first principles. And… uh oh. It appears I've activated my own pet peeve. ↩